Incipient

A Collection of Lyric Essays

By Andrea Summers

Contents

Preface

I hope to become unflinchingly whole in this lifetime. That is, I want to become unflinchingly honest; honest in my sorrow so as to meet joy with rawness; honest in my confusion so as to procure clarity; honest in my fear so as to draw it near and strengthen in its proximity. To become truthful–that is my ideal.

Within and around me there is a tendency to shy away from the truth, to be wary of it, to bend and manipulate it into some superior untruth. But attempts to bend the truth only bend the things around it–perceptions warp and minds strain and intentions twist and trust folds–all while the truth remains intact.

I understand dishonesty. The truth is an uncompromising thing and we use subjectivity to skirt around it, soften its edges, ignore its complexity. Dishonesty as it is embedded in social conventions creates a platform for cooperation where dealing with the truth might cause disruption. But disruption is abundant regardless, and blind devotion to cooperation and niceties is a barrier to positive social change. The truth is, rigid adherence to the standards of expected social cooperation reflects a calcified fear of confrontation with reality and each other.

We are sensitive and vulnerable creatures by nature. But we struggle to reconcile with this reality–we want to be strong, invincible. We have become vigilant to anything that threatens our imaginary superhuman status, and honesty is the foremost intimidation. So we make the truth a taboo and compartmentalize reality so that we can continue living in a dream. But we are not truly content with this dishonesty, this ignorance, this blindness. When we are asked ‘How are you?’ we answer ‘Living the dream!’ to be nice, to be cooperative, when in fact we are stuck in a waking nightmare.

I have struggled with social interaction for as long as I can remember. Early on, I realized that many of my experiences and circumstances were socially unacceptable. I couldn’t talk about what was going on at home, or in my head, or with my body. I couldn’t talk about my reality. So dishonesty in the form of masking and people-pleasing became my means of connecting with others. I constructed a version of myself that was digestible. So I understand dishonesty. I have relied on it. But I learned that dishonesty is not reliable. It draws a wedge between trivial ideas of good and bad, making you unwhole, shattered.

I understand at a personal level that dishonesty is a defense mechanism that always leads to destruction. And I have observed this to be true at a societal level as well. When we are dishonest about the reality of oppression and hardship, we enter a dream where we don’t have to confront its proliferation. We protect ourselves with ignorance and pretend we don’t know it as the main weapon wielded throughout history.

I want to heal in this lifetime, make myself whole again and help others do the same. I am no expert of the truth. I have a lot to learn about honesty and reality and how to be of service in mankind’s reconciliation with our sensitive and vulnerable nature. I write in the spirit of learning how to be honest. Here, I present an incipient confrontation with truth.

Words from Toni Morrison

From her 2003 interview on "Love"

“I would like to say something about how hard it is and how necessary it is for us to become and to remain humans. That means a lot. It means not giving in to the comic book version of who we are, not giving in to all this medieval rhetoric…We know deep down what’s right, and what’s true, and what’s needed. We’ve got to get there. We just have to.” —Toni Morrison

A Late Sapling Friend

The biggest blessing I’ve had in life is being raised in the country, surrounded by nature. I grew up in between two small towns in rural mid-Michigan. There were eight houses in my neighborhood and we were surrounded by fields of corn and soybeans and mint. My house was on four acres of property, three of which sat behind our fenced-in back yard and were called “the trails” because we mowed walking paths through the overgrown plot of land. Apparently when my parents bought the house, those three acres were a big, flat, grassy field. As far back as my memory goes, they were filled with young pine trees and large raspberry bushes, complete with trails for exploring the small forest. I can’t imagine it flat and empty.

I loved the trails so much. They were my world, my playground. In elementary school, when the black raspberries would ripen in the hottest part of the summer, my mom and I would wake up as early as we could and bring big popcorn bowls outside to pick them before it got too hot. It was important to leave while the morning air was still cool because we had to wear long sleeves to avoid getting torn up by the thorns. The wild raspberry bushes were endless, lining most of the trails, and their fruit ripened faster than they could be picked.

When it got too hot or our bowls were full to their brims, we’d head back to the house sweating, our lips stained purple. Many days we’d part at the gate of the fence between the back yard and the trails because she needed to go inside away from the heat, but I wanted to stay out and play. She’d take the bowls and shut the gate behind her, then I’d skip as high as I could back to the front area of the trails. That first half-acre was the only part that was still flat–a small, grassy clearing. It was separated from the rest of the trails that were filled with pine by a row of mulberry trees–which were also fun to pick but not nearly as delightful to eat. Bland. Sometimes I’d go and check on the grape vines that grew between our trails and the neighbors’. I remember learning they were grape vines and being astounded that we had them growing on our own property. The grapes never fully matured, they’d grow in green bundles and we’d be lucky if near the end of summer a few would turn purple, though still small and incredibly sour, bitter. I would suck on those ones and spit out the large seeds. That little plot of grassy, flat land was where I’d decide to grow my very own tree.

I’ve never known what kind of tree it was that I grew. It started as a seed that everyone in my class received–probably around third grade. We all put our seeds in a bag with a damp paper towel, taped to the classroom windows until they germinated. Then, we moved them to little pots of soil until they grew about a foot tall, and when summer began, we got to bring them home and try to keep them alive on our own. I was so excited the day I brought mine home. I had hated leaving it at the school all alone every day since it started growing. Pulling into the driveway on that last day of school, I excitedly gathered a few items I’d need: a hand shovel and a watering can. I filled the watering can and set out for the grassy plot of land at the front of the trails. I set the little sapling in its plastic pot on the ground next to a nice flat area where I could see the dirt through the long grass. I ripped the grass away from the ground and stuck my shovel in. It was hard to dig, but my tree’s pot was only a few inches tall so I only had to dig a few inches deep. I was sweating by the time the hole was ready and the cicadas had sung a few verses in unison. Wiping my forehead like I’d imagined a farmer would, I carefully guided the sapling out of its container, the wad of its roots catching in the drainage holes at the bottom. Once it was free, I placed it in the shallow hole and watered its base so I could mould its soil to fit its new home in the earth. I patted the ground around the plant a few times, proud.

You’re finally home with me. I’ll take care of you. I reassured the plant telepathically and smiled at its warm response, silently thanking me. I’ll be back tomorrow, I told her.

It was extra hot that day, so I dumped the rest of the water from my can into the ground around the sapling. I ran off to play then, fondly imagining the tree growing with me, faster than I could grow, eventually beating out my height.

Two days later, the second day of summer break, my eyes suddenly widened as I halted my play in the back yard. My tree! I had forgotten it yesterday! I got a bad feeling instantly. My own body was much larger than the sapling’s and I was dying of thirst after twenty minutes outside. I grabbed my watering can from under the back porch and filled it up from the hose spout on the front side of the house. I hurried back to the back yard, through the gate to the trails, and into the small grassy field. As I approached the little circle of dirt I had cleared out for my tree, I dropped my can to the ground in instant defeat, the water pointless now and spilling out into the dry ground. There in the middle of the bare circle of dirt was my tree, or what was left of it. Now, it was just a yellow, dry stem sticking out of the ground, stiff. I was huffing as my face turned to a frown and I dropped to my knees.

“No! No!”

I plucked the stem, now just a twig, and not even a single root came up with it. They were shriveled and gone. I held the dead little stick in my hands and stared at it, my brain racing to think of how I could fix this. I couldn’t. No one could. I couldn’t run crying inside to my mom and make her bring it back to life, make it grow taller than me like I had planned so I could climb on its limbs. My tree was dead and gone and all that was left was this stick. I felt panicked as I ran back to the house, climbed over the pool ladder that let me and my siblings scale the fence between the front and back yard, and finally stopped by the side of the house where it was shady. I sobbed into the dry stem in my hands and felt its life being severed from mine, not to return. Finally, with no ideas of how to resurrect my friend, I laid her down in that shady spot next to my house in the dirt that was still moist.

I had planted her in the open, grassy part of the trails because it was the only part of our property that wasn’t already filled with trees. The young pines dominated the trails, which were lined with mulberries before the willows took over the back yard and the maples and old, mighty pines took the front. Now, on the side of the house with the cluster of maples, I scorned myself for not planting her here. The ground was moist here, not scorched by the sun. The maples didn’t even take up that much space–they would have left room for her to get the sunlight and water she needed. I should have known the fate I had set for my sapling when I planted her in the middle of yellow, dry grasses that crunched under my feet. I shouldn’t have forgotten to water her the day before–her first full day out there, all alone. Probably waiting for me, thirsty. How many glasses of water had I drunk that day without thinking of her even once? Just one of those glasses probably would’ve been enough to get her through the day. And if I had remembered to go out there to check on her, I would’ve seen how thirsty and frightened she was there all alone, and brought her to a better spot, this spot next to the house in the shade with cool soil and live neighbor trees. Why had I kept her away from the other trees? I guess I thought they’d steal her water, take her sun away. But they hadn’t. I had stolen her water, made her die alone. Maybe the maple trees would have helped her, connected her roots into their big underground system and sent her just as much as she had needed. Maybe I should have let them take care of her instead of taking her on as a project for me to develop on my own with pride. Maybe I should have treated her like a tree, and not another lonely kid like me. I laid her to rest in the shade there by the house with her maple friends.

I’m sorry. I let you down. That’s all I could say to her.

I cried more and eventually told my mom and she probably got me to forget about it all for a while, but I’ve thought about my little sapling friend my whole life since then, missing her. Wondering what she would’ve looked like if she had grown bigger than me.

I’ve never known what kind of tree it was that I tried to grow into a friend of mine. When I went searching online today, I found that my sapling friend looked a lot like a honey locust. The honey locust tree is native to Michigan and grows long thorns on its trunk and branches. According to wikipedia, their thorns probably evolved to protect the tree from “pleistocene megafauna” aka massive mammals of the ice age including the mastodon. There’s also a honey locust moth that lays its eggs on and eats from the honey locust tree, and develops different types of thorn-like horns throughout its larva phases to deter predators.

It’s too bad my sapling friend never got to grow into a big, thorny tree, fending off large-tusked creatures and providing food and shelter for smaller horned ones. I think I would have fit in with the mix quite well. Sometimes I feel like I’m covered in thorns too.

Corners in Rooms

When I was growing up, there were no corners in rooms.

They were rounded at the edge, mounded.

I could climb to the sky, touch the ceiling fan.

Collect its dust, breathe it in.

I could see the whole room from a mountaintop;

Dig a tunnel if I wanted.

Now rooms are flat and sharp, cohesive.

They smell clean and I can breathe.

I can put treasures in the corners, a sofa or two.

Now the rooms are for me.

And sometimes I hear an echoing.

But it’s only empty space, beckoning.

Home

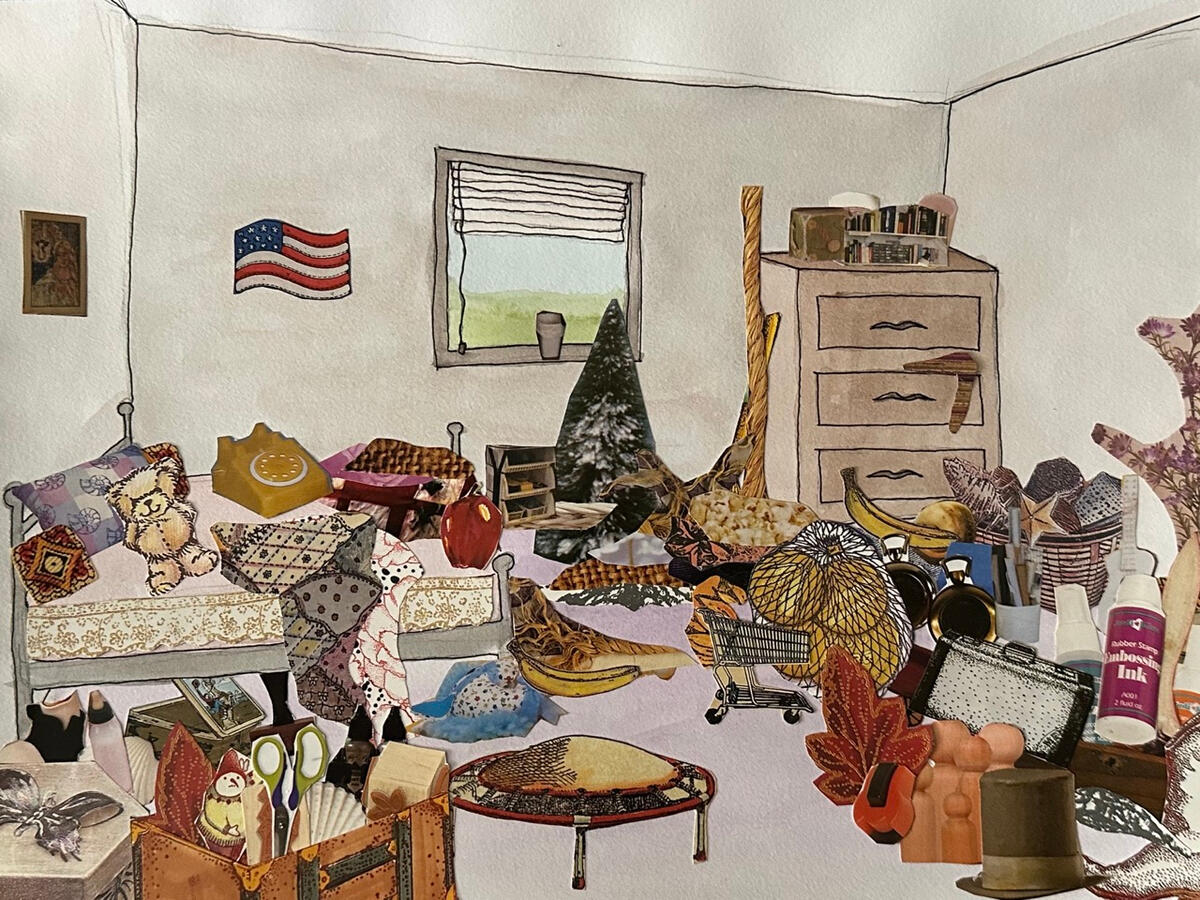

My family moved out of my childhood home and into the vacant half of my grandparents’ duplex in the summer before I started high school. The move was sudden; I only brought one box full of my stuff and at the time I didn’t realize we were moving because my parents had finalized their divorce and my dad got the house instead of us. I didn’t think about the house or miss it much until a few years into college. I was a young teenager at the time of the move and all I was focused on was the fact that my grandparents’ duplex was closer to town where my friends lived, it had wifi, and most of all–it was clean, nearly empty. This last point was significant because my mom was–or rather is–a hoarder. I think this was part of the reason I didn’t care to look back in my memories at the place I grew up until recently.

A few years into college, when I’d turn off the lights and close my eyes to sleep, I’d start thinking about the house again and mapping out what I could remember of it. At first, there were just the dominant memories of my bedroom and the living room and yards, but as I mentally walked myself through each room, I started remembering all the nooks and crannies, all the piles of junk and the pathways through them. This was entertaining to me, nostalgic.

My freshman year dorm and the house I shared with three other students the next two years were not like my childhood house–they were messy, sure, but not hoarded. Growing up, people weren’t allowed in our house. A small handful of times a neighbor or a close family member would stop over, but especially as I grew older and the rooms became more and more piled up, we stopped letting people inside. I had two sleepovers as a kid. The first resulted in one of my best friends being banned from returning by her parents and the second was only possible because my remaining best friend had a comparably dysfunctional home life.

I wasn’t able to start this mental exercise of revisiting my childhood home until I told the first ‘outsider’ that my mother is a hoarder. I started dating my partner just before I entered college, and after a year of being together and avoiding taking her to visit my family’s home, I finally broke down to her and admitted the deepest source of shame within me. Her unwavering support allowed me to start processing this part of my reality and open up to my therapist about it, and now I am finally able to be pretty open about it in general. My mom’s hoarding has marked my identity and mentality deeply. I have fondness for our first house because while it was hoarded to a point of great shame for our family, at least it was ours. I only have shame and embarrassment for the half of the duplex we lived in while I was in high school, because that was my grandparents’ house, not ours, but she ruined it all the same. My childhood home was ours alone; just me, my siblings, and my mom lived there, and it was out in the country, private. Our secret was safe there. And I grew there, dreamed there, was little there, spent years there before I had accumulated such immense shame. I remember years of feeling free there, ignorant to the fact that my freedom was a form of neglect, isolation, that would have later consequences.

I have now talked about my childhood home with my partner, therapists, and friends. I've revisited it late at night in my head. I’ve even revisited it in real life once. I didn’t go inside, because a new family had lived in it for years already, but seeing it again only deteriorated the image in my head because the new occupants had covered the pretty dusted-rose paint of the exterior with a dark grey and dug up the willows and pines that made it magical in my memory.

I find portrayals of hoarding in the media distasteful; they seem more like caricatures than genuine representations of what hoarding is like. People know about hoarding mostly because of shows like Hoarders which sensationalize the phenomenon, exploit the suffering families of hoarders, and serve as trauma porn. There’s also an obvious personal edge to my disdain for these portrayals–I feel ashamed as I scroll past the shows that I feel were made to expose my wounds, to taunt me in front of my friends. There is some worth to the existence of these shows, they bring a form of awareness to an issue that is largely considered taboo and not talked about in public. I don’t remember when I learned there was a word for what my mom was doing in our house, but I probably found the word because of these shows, and having a word for it helped me understand my experience and connect with others who shared it. But the representation of hoarding in these shows comes from an outside perspective, and it’s uncreative. I have never seen creative representations of my experience, and the experiences of the children of hoarders are a world away from that of the hoarders themselves. The hoarders create the hoard. The children grow up among the hoard, the hoard is the world we are brought into, the mess our childhoods are tangled up in. My imaginary friends emerged from the hoard, my crafts were made with items I dug up out of it, I fell asleep every night among it, my body grew along with it.

I think that actual pictures and videos of hoarded houses do little to represent my experience growing up–they create a spectacle, an image that people can look at in awe and think: how could you live like that? I didn’t look at the hoard this way. I was familiar with it, it was home, it was normal. I didn’t look at it and see mounds of junk. I saw last Christmas’ decorations and my baby clothes and toys and crafts and vases with dried flowers I picked for my mom two summers before and my bed and my wardrobe and my life. I have tried drawing it to translate my view, but it only ends up looking like scribbles. This year, I got the idea to recreate it through collage, and after trying it out, I think that’s been my most successful attempt. So here’s my childhood bedroom, as the hoard grew throughout the years, how it looked through my eyes.

There was a point when, during one of our “spring cleaning” attempts,–which actually meant piling the junk from one room into another to try and make some living space–my room turned into one big mountain. I stopped living in my room then, my bed was buried deep under boxes of clothes and trash and broken TVs, and probably started sleeping in one of my siblings’ rooms or on the couch. Access to my room could disappear in a day and my belongings could get lost under a pile for years. I got the sense that nothing really belonged to me but I was somehow still responsible for everything. The words hoard, hoarder, hoarding were never used in my house. If they were, that would mean our situation could be traced back to a mental disorder, and that mental disorder could be traced back to a person, my mom. But it was never her issue, it was ours. Most of our “spring cleaning” days followed one of my mother’s meltdowns about the state of our house which were triggered by some mess that she blamed on me or my siblings.

I remember one morning after a routine sleepover at my cousin’s house, my uncle brought me the phone and said my mom was on the other end. When I picked it up, I could instantly tell it was going to be one of those days. She told me that she had gone into my room and seen the pile of clothes I had shoved behind my bed. I was frightened by her tone and her demand that as soon as my siblings and I got home, we got to cleaning immediately. I gave her the best response I could think of to calm her down, and I couldn’t begin to process my confusion until after the call. I didn’t understand why she was freaking out about my messy room all of a sudden; my floor had been covered in piles of clothes and miscellaneous items for years and so was the rest of our entire house. There was no way for me to express my confusion; I knew she would take that as defiance and the last thing I wanted was to trigger her more. The day was already going to be hard enough. So I repressed it. And the pattern of repression proliferated for years and years, my frustration and confusion and isolation and fear could only be shoved down. My mom’s outbursts never led to any part of our house actually being cleaned, because in reality the mess was a result of her own mental disorder and her meltdowns were her best attempt at coping with everything she was repressing herself.

I never got to have my own meltdowns. No childish outbursts or breakdowns over my own emotional turmoil. I kept my emotions tidy and easy for others to deal with. There was no one to put them back in order and they were just another mess that I hoped would go unnoticed by my mother. Things are different now that I’m removed from the disorder of that house and of my mom’s unhealthy coping mechanisms. Being open with my partner about my experience helped me turn my life around. I let myself have the long overdue meltdowns now, and I have a safe person who will help me make sense of things. We keep our home tidy and we don’t pretend our emotions are easy to deal with. They’re not, but we work through them instead of repressing them, instead of letting them pile up until they eventually explode.

I still think of my childhood home fondly as humans tend to do with anything nostalgic. I still keep my emotions tidy around my mom even though she expresses regret over how we were raised and encourages me to confide in her. We tend not to grow out of our childhood habits easily. But I am creating new habits and leaning into self-expression, trying to make up for all those years of repression. Parts of me got lost in my mom’s hoard, buried underneath it. I think I started mentally revisiting my childhood home to look for those parts that were left behind, once it was safe to want them back. I think I’m constantly looking for ways to dig up those buried parts of myself, to let them know it’s safe to come out now.

Some thoughts after a restless night and depressed day

I’ve always gotten offended when others imply that they know me, what I want, what I’m thinking. I feel as though no one’s ever really known me–the real me, inside, the one who has seen it all. How dare anyone think that they know me when I’ve been forced into hiding my whole life? I never really wanted friends growing up, not the human kind, but people were drawn to me, clung to me, claimed me. And for a while it was easier that way–to pretend that I was known. I had one real friend in elementary school. I think we got along so well because she was the only other person I knew who couldn’t really talk about her home life. She did talk about it with me, and that’s why she was the only friend I ever felt comfortable having in my home–my secret, disgusting, shameful home. I remember lying next to her on a mattress on the floor of my brother’s bedroom in fourth or fifth grade and her confessing to me that she was queer. I remember swallowing hard and feeling like crying. I remember feeling like I had something to say back, but I couldn’t. There’s a lot I’ve wanted to say in my life that I couldn’t, never got to. So much left unsaid. Am I supposed to want to say it all now, now that I’m allowed to? To whom?

My head is filled with dark places but that’s not such a fun story. I spill out anything that leans into intellect, humor, validation. All of my interactions are tailored to the other person’s likings. What is there to do with the memories, the knowledge, the terror of those dark places? Put it out for the world to see? Keep it inside forever? Keep it confined to the late-night confession sessions with my partner and just let that be enough? I don’t know how to be heard or seen in the way I want to. My life has never really been about me. It’s been about being good, nice, unnoticed, stretched thin, invisible, malleable. I am like a thin sheet on a clothesline that gets blown horizontal in the slightest wind, becoming undetectable at eye-level. I get left outside when everything else is brought in. The earth below and the skies above see me clearly, but none of my kind do. Do I want them to?

When I write, I feel like a pessimist. I know the dark places want to be brought into the light but how? To show to whom? I have never liked an audience. I am received well when I am unknown or altered. I spin in my head all day thinking of ways to reconcile with those who have pushed me around, hard. I imagine how I could fix my parents without blaming them. They must have had it hard too, right? There are so many questions I wish I didn’t have to ask to get the full picture. Did Grandma scream at Mom the way that Mom screamed at us? Did Dad know his dad any better than I know mine? Did either of my parents ever think before they decided to have kids? Who decided? Why didn’t they decide to stop after the first time Dad had to move out? I wish they would have taken care of us in a more meaningful way. I wonder if they could have. My mom used to joke that I was like Matilda because of my ‘self-sufficiency’. I was like Matilda. I was left all alone and forgotten about. I guess I never left myself behind, not fully, and that’s something. I’ve always been looking for myself. In movies and books and youtube videos and comment sections and reddit forums and in nature and abandoned buildings and on my bike and in my earbuds and in the split second of blissful terror right when the car has crashed and you haven’t registered it yet but you see it and you feel it in every nerve of your body. I look for myself in my writing, and here I am. Who the fuck am I? Who is putting all this together? How do I know anything, why? Why do I hold on to so much and how do I let go? Will there ever be a conclusion to these loose ends? To the things that happened in the basement or in the dark or in the back room that no one ever wanted to talk about? Aren’t you supposed to talk to kids when bad things happen to them? I never got to be the victim in the story when I should have. Always the witness, the perpetrator's accomplice, the middleman, the bitch, the savior. Will there ever be anyone who remembers the things that happened to me besides me? Does it matter at all–would it really change anything if there was someone else to know it all? It’s mine, I just don’t know what to do with it. I’m comfortable in the dark but others don’t seem to want to sit in it with me. I just want dark and quiet all the time. I love the feeling of waking up from nightmares because I can think, “it was all just a dream.” I think I spent my whole childhood waiting to hear that, but it wasn’t a dream. It was real. And I wouldn’t change it or be someone else if I could, but fuck, man. Fuck.

A Gen Z Dilemma

In 2012, after much begging, my mom bought me a fourth-generation iPod touch from a garage sale. I was nine years old, in the fourth grade, and my mind was boggled at the possibilities of this compact device. The same year, I discovered social media, and ever since, I have spent significant time evaluating my appearance through the front-camera lens of various touch-screen devices. The image that illuminated back at me has always carried a heavy presence of onlookers–an always perceiving audience. It makes me cringe to know that I exposed myself to public observation at such a young age, though it is a sign of certain positive growth that it is no longer the idea of others having witnessed my awkward progression into puberty that bothers me, but rather the knowledge of the damage that exposure has done to my sense of identity. I lost the ability to see myself clearly through the camera lens.

Since nine years old, I have filtered my self-view through the perceptions of others, whether assumed or asserted. This is not a particularly uncommon experience, especially for women in regard to physical appearance. Society has never held back from reminding the woman of how she is to be perceived and how she is to be treated if she falls outside of those expectations. But social media has entirely reshaped that experience. I was born in 2003, and like many of my gen-z comrades, the formation of my identity happened largely online. Instagram was less than two years old when I downloaded it for the first time. I remember standing in the hallway with my friends on the last day of the school-year and hearing one of them mention ‘instagram’ and instructing another to ‘follow’ them on it. Elated to have acquired my very own iPod, I connected to the school’s wifi and downloaded the app myself. I fumbled my way through the sign-up pages and asked my friend for her username. She announced each character for me to type into the search bar, and I remember the puzzled look I gave her as I asked, “What’s an underscore?” That was the beginning of the end.

Social media dominated the next decade of my life. I got my first boyfriend on a messenger app, learned the inner workings of sex, created fan pages for queer youtubers and various Kpop boy-groups, socialized with teenage girls and forty-year-old men, and became absolutely obsessed with my appearance. I was a shy kid and tried to be modest about my indulgence in posting selfies, but always silently craved feedback in the form of likes and comments that would indicate my desirability, the worthiness of my physical form. The exchange was fundamentally flawed–likes and comments from girls usually indicated their longing for reciprocated validation, and those from boys usually indicated their raging hormones I was completely unaware of. And it was rigged–those whose natural physical features resembled those sensationalized in the media automatically won the disguised competition. None of it had to do with our worth, but the idea that it did is ingrained in my generation. Likes and comments are social currency, and in the age of TikTok and invasively personalized algorithms, they are literal currency.

In middle school, my friends and I ran a shared instagram account where we posted about queerness. We were all questioning our sexualities for the first time as puberty hit, and we were big fans of Dan and Phil, Tyler Oakley, and Troye Sivan; so naturally, we fell into a queer online space. Running that account with them was fun and exciting. We lived in a small, conservative town so we kept it secret from our classmates but gained a decent audience of just over a thousand followers over the course of a few months. We posted about youtubers, made friends with queer kids from around the world, and got the attention I think all of us craved but were deprived of in the social circles at school. I got a pixie cut inspired by other queer teens I saw on instagram and tumblr and went to two Troye Sivan concerts–I was really growing into my queerness. But part of me was crushed when eventually I got outed because a group of ‘popular’ kids at school found the account and classmates started asking me if I was gay. I was scared and embarrassed and denied the accusations. We all stopped using the account around that time and I spent the next few years feeling haunted by my appearance. I started getting cystic acne and I felt dysphoric as my hormones kicked in and all the other girls suddenly had boobs and boyfriends and all I could think was why did I make myself look like a boy? My own breasts were invisible and my pixie was creeping down my neck into a mullet.

In high school, I found refuge in online anonymity. I became obsessed with Brockhampton and Kpop boy-groups and spent hours posting about them every day on instagram and twitter. I didn’t share pictures of myself anymore and made sure all of my profiles were private and undetected by anyone at school. I made friends with other teens who obsessed over the same music as me and similarly almost never posted their faces or talked about their personal lives. Though that time was filled with self-loathing because of my insignificant status at school, online anonymity brought me close to a true sense of belonging for the first time. I got to spend hours talking about the things I loved rather than scrolling through a feed of my peers’ faces that I had already deemed better than mine. I transformed the rejection I felt from my peers into a sense of mysterious superiority–something I think a lot of ‘outcasts’ have to do. I forced myself to see my differences as intentional, nonconformist, alternative. And being chronically online, I was often aware of and taking part in trends that hadn’t hit rural mid-Michigan yet. I think I was the first kid in my high school to wear checkered Vans, so yeah, I privately considered myself pretty cool. Tragically acne-ridden and stuck in the awkward stage of hair growth, but still cool.

It was only after my hair had finally reached my shoulders again, I had conjured up the money for a beastly Victoria’s Secret pushup bra, and eventually got sexually assaulted a few times in late high school that I decided my appearance was finally worthy again. I was on the cusp of true womanhood. At the end of my junior year, just as I began to consider myself desirable, COVID-19 hit. My mental health had just been shattered by the recent string of sexual violence by my male peers, and now a worldwide pandemic demanded extended social isolation. Thankfully, the assaults made me hate school so much that I embraced the stay-at-home order with a great sense of relief. And 2020 was the year that tiktok became huge since we were all stuck inside with nothing to do. I made an account and my second video went viral, getting millions of views. I gained four-thousand followers and though the original video was a short clip of me pranking my younger brother, I took it as an opportunity to funnel validation towards my appearance. My body was finally maturing in ways I found desirable and my growing hate for men helped me embrace my queerness once again. I had a relatively significant following online, and this time, having an online platform wasn’t just something the weird kids did–it was now the dominant social space for my peers. It was the perfect storm for me to become what I thought was my final form: an alt girl.

At that point, being an alt (alternative) girl on tiktok meant you were likely queer, wore dramatic eyeliner, had dyed hair, and listened to musicians outside of the mainstream or before they entered the mainstream. I embraced this identity; it felt like a rite of passage as an unpopular gay girl who grew up in a small town and would soon be leaving it. I milked the fleeting bursts of validation by posting lip-syncs and thirst-traps, exploiting my growing body and keen ability to follow trends. My acne was clearing up and I started wearing wild makeup and dyeing my hair purple and pink and blue. I never had to go back to school in person because of the pandemic. With the pressure of fitting in with my peers and the norms of my conservative hometown falling away, I was able to relish in the attention I got online. Getting attention from other queer people made me feel like I was finally worthy of flaunting my appearance, using it as a tool to control how others viewed me.

With a growing sense of agency over my physical appearance and an impending move to the city to start my undergraduate studies, I felt that the power to reconstruct my identity was finally in my hands. I would no longer be the shy girl to be overpowered by male aggression, nor the daughter hiding her sexuality from her father’s Catholic family, nor the awkward friend that went unnoticed in a room full of people. I would move to the city and be like the city people, powerful and attractive and desirable. And I did it, I went to college with blue hair and a perfected winged eyeliner that made me feel fierce and notable. I mingled and nodded when others nodded, sneered when others sneered. I fit in with the crowd that would have been rejected at my high school but was considered cool in the city. I boasted my rebellion, but to a fault.

I spent so much time trying to climb a hierarchy where I thought I belonged, one that I believed was free of the corruption of conservatism and conventionality. But hierarchy was the corruption. I had grown so familiar with the crooked morality underlying conservatism that I had mistakenly assumed that beneath the surface of alternative culture, queer culture, contemporary culture, I would find a sanctuary of unmarred integrity. I thought I could take refuge in an unfaltering morality held by rebellious spirits; that it would back me up when conflict came about and I’d have people on my side for once.

I was wrong. Growing up feeling rejected by the people in my hometown made me cling to the idea of a people that would accept me, and I tried to assign this role to the people I found in the city. But they never promised me protection or acceptance, and if I hadn’t put them on such a high pedestal, it wouldn’t have been hard to see that I wasn’t going to find the morality and safety I was looking for in any kind of alternative hierarchy. Many of the cool people I met in the city either shared a similar background of rejection and abuse and were just as clueless about how to forge healthy relationships as I was, or they were used to being considered cool, at the top of their own hierarchies, and had no interest in extending acceptance to pitiful, lesser creatures like me.

Within queer and alternative spaces, I found a painfully familiar disinterest in moral consistency within social relations and sexual manipulations. I realized how ignorant I was to expect that prejudice would fall away in the spirit of rebellion and resistance. For a while, my faith in humanity was shattered. My view of the world became shrouded in judgement and disdain, but that view was a projection of my internalized fear of abandonment. I was looking for acceptance from others, but in my perceptions of immorality, I felt an acrid rejection extending from my past.

My options in relating to others were to cling or to be rejected, and I used my judgment as a safety net to predict the trajectory of my relationships. But I didn’t see that my judgment was tainted by cruel but not unusual mistreatment, and that there were other ways to relate to people. Whether I was clinging to others or being rejected by them, I was missing the self-esteem fundamental to developing meaningful relationships. I was always looking outward for others to determine my worth, to make the rules, to tell me where to stand in line. Constructing my identity and advertising it on social media kept me in these ridgid patterns. Posts and likes and comments and follows reinforced my obsession with external validation and fitting in via appearance. But once I learned that fitting in wasn’t the same as being accepted and that appearance didn’t point to morality, social media became a maze that I was dizzy from trying to navigate.

[Blank] went to [blank]’s party last night.

When was the last time I went to a party?

A long time ago.

Why so long ago?

Because I don’t like parties, they’re too loud and I can’t stand small talk.

How will I ever be as known as [blank]? How will people remember to like me as

much as they like [blank]?

They won’t.[Blank] posted a picture of the hangout I decided not to attend because I wanted alone time.

I can tell by the look on their faces that they bonded, their connections grew stronger.

I’m falling behind. Everyone is getting closer and I’m at home all alone.

I guess I’ll give myself less alone time, even though I feel like I need more.[Blank] posted drunk mirror selfies with their friends. They’re all laughing and holding onto each other.

I should drink more.[Blank] posted [superficial political opinion].

I should care about that.

I should post about that.

I’m ignorant about this subject but who am I to just scroll past something that seems important?[Blank] posted a selfie.

I should take a selfie.

I don’t like how I look.

I should take another selfie.

I don’t like how I look.

I should take another selfie.

I don’t like how I look.

I hate how I look.[Blank] is posting about their creative endeavors.

Why don’t I post about my creative endeavors?

I’m afraid of what people will think.

I must not be good enough.

I need to work harder.

I need to do better.

I need to be different.

What a nightmare! Social media was poisoning me and I was addicted to it, to constantly evaluating my worth by comparing others’ constructed identities to my own. And this online battle wasn’t confined to social media, it infected my entire life. I used standards set by social media trends to decide what I wore, what I believed, how I felt, where I went, how I acted, who I associated with, how I spent my energy, and how I treated myself and others. And it was empty of true meaning–an endless maze with no escape. I felt trapped and suffocated. But I knew that in reality, I was not trapped, that social media was a maze that I put myself in, and that I could therefore take myself out of.

I had been addicted to social media since I was nine years old, for an entire decade, and I could barely remember what life was like before it. But it was making me sick, so I took the risk of finding out. I deleted instagram and tiktok just before I turned twenty. Stepping outside of that maze felt like freefalling. The main connection to the social circles I had entered fell away, my constructed identity fell away, my sense of control over how I was perceived fell away. I realized that I hadn’t just forgotten what life was like before I had social media, I had forgotten what I was like.

In my withdrawal from social media, I was forced to face myself directly. Not the version of myself that could be understood through labels in an instagram bio or the inverted image from my front-camera lens. I had to face what I was feeling in my body, what my inner-dialogue was communicating, what memories my mind clung to without the luxury of distraction. And it wasn’t a delightful discovery–I found my body aching with pain and tension and my mind filled with self-hatred, doubt, and recollections of unmourned loss. This space where I felt myself viscerally was dark and lonely; it scared me, but somehow, it was homelike. It was real. It was me.

No wonder I was so afraid of abandonment all those years I tried to get people to like and accept me through social media–I was abandoning myself the whole time. I was advertising a version of myself that wasn’t real–someone who was confident, joyful, energetic, carefree. I spent so much time advertising this persona that I forgot there was an original version of myself. And the original me shriveled up inside with all her insecurity, sorrow, pain, and fear, with no one to witness it. I tried to bury her, but she was always there, even when I was pretending to be someone else. She had been imprisoned by cruelty but vigilantly waited all those years for some unbreakable morality to signal that it was safe to come out.

I wanted my original self back. I didn’t have perfect morality or any other form of paradise to beckon her out with. So I offered what I could: to bear witness to myself. No longer advertising a version of myself I thought better than the original, I could finally begin to make room for remembering the things I tried to forget and feeling the things I tried to reject. I started to get glimpses of myself not through the lens of social media trends but through the reality of the experiences I’ve had. And for the first time, I stopped depending on a dream of the world one day engulfing me in a morality that would justify my existence.

In the hours that were no longer drained by screen-time, I began reading and writing more, sitting in silence more, and taking more time to be alone. This wasn’t easy either. I had to learn how to be accepting of the negativity and uncertainty of my thoughts that boomed in the silence. I had to learn how to live with the guilt of taking time for myself instead of pacifying it by pleasing others. I had to admit to friends that I couldn’t keep being the person they thought they knew and loved. I had to lose friends. I had to learn how to make new ones by means other than self-sacrifice. I had to be open to a new version of myself emerging without resorting back to the one that I knew others would like. I had to learn how to find more value in being myself than liking myself, because likeability is not always compatible with honesty.

I don’t really take pictures of myself anymore, and to be honest I kind of forgot how to. I feel silly posing for a still frame because I notice the old habits of adjusting my face to appear some particular way. But I love looking at my reflection in the mirror now. I don’t look for beauty there, but for something behind my eyes. I struggle to make eye contact with others because I have a bad habit of looking for expectations to meet in their facial expressions. But now, when I look in the mirror, this habit turns into something beautiful. It turns into the question: what does she want? And without the distortions of makeup or hair dye or fancy clothes, I look like I did when I was a little girl again, and all she wants is to be herself. And there is such ease in wanting nothing more than to please that little girl, my original self. And I know that I am finally starting to see myself clearly again.

Midnight Return

Oh I forgot

How the night sky made me feel small

The stars gave perspective

With myself below

In the city I ask

Who am I? Why are we here?

But out of the limelight

I used to know

Words from Voltairine de Cleyre

From her 1885 poem "The Burial of My Past Self"

"No, Heart, I would not call thee back again;

No, no; too much of suffering hast thou known;

But yet, but yet, it was not all in vain—

Thy unseen tears, thy solitary moan!

For out of sorrow joy comes uppermost;

Where breaks the thunder soon the sky smiles blue;

A better love replaces what is lost,

And phantom sunlight pales before the true!

The seed must burst before the germ unfolds,

The stars must fade before the morning wakes;

Down in her depths the mine the diamond holds;

A new heart pulses when the old heart breaks.

And now, Humanity, I turn to you;

I consecrate my service to the world!

Perish the old love, welcome to the new—

Broad as the space-aisles where the stars are whirled!"

—Voltairine de Cleyre

The Taking Up of Another's Idea

Today I seek to be free, to break out of rigidity and into spontaneity. What does my body want? A space clears in my overactive mind to ask the simple question, and I know I am to feel the air. Spring is blooming out of winter’s melt and today brings the first warm wind. I reach for my bike and my mind is flooded with the possible burdens of a short ride around the neighborhood. I mustn’t meddle with these thoughts or embody them. Today I seek to be free. So I will not settle for the confines of this porch in fear of being seen by others. And I will let the door stay unlocked instead of scurrying inside to retrieve a keychain that will be a bother to carry and brings to mind the idea of imminent robbery which is rather unlikely. More than weighing out the possibility of being robbed, I am concerned with freedom; with having a short bike ride without a bit of paranoia dangling behind me; with knowing for just a few minutes the body-feel of not being caught up in some neurosis.

I set off and the wind feels wonderful on my face, my body mobile and movements fluid. The push of peddling is transcended by the forward momentum it produces, much unlike the exchange between mental energy and autonomy. I revel in the effortless glide and the easy temperature ushered to me by unseen forces; mass and velocity and friction mingling. I feel grounded in the physical until I hear my name called out from behind a neighboring apartment building.

And-rea

I’m snapped back into my mind and I shake my head, feeling the burden of the call. But it was not anyone calling for me, it was a loud beep-beep from a nearby truck. I decipher this much as the sound plays back in my head, devoid of language. I know why I’ve heard my name. I know it is because my mind cannot stand to be carefree, and it knows just how to provoke caution. Attentiveness is ingrained in me, the incessant demand to attend to others’ needs and desires. It manifests in people-pleasing, masking, obedience, hypervigilance, overperformance, disingenuity, rumination. I’m always trying to figure out what people want and how they expect me to respond. This tendency was born out of the powerlessness of childhood, but in the agency of adulthood, has become a sour dose of paranoia running through my veins. There is no one calling for me, beckoning my attention here on this bike ride, but it is easier for my mind to conjure a demand out of automobile sounds than to tolerate a single untethered moment.

Bound to demands, I am always considering others’ ideas of must and must not, should and should not. In this realm, nothing is free, but all is structured, and I have confused structure with safety. It is too much to bear to act freely and see what comes of my action; I have become complacent with reacting to others’ actions, being what becomes of it: agreement, validation, concern. This way, I can ensure a happy ending for others. Not for myself as I have no beginning or end in these matters, but I am able to prolong my own sense of safety this way. As long as I meet demands, I can keep life as I know it from crumbling before me.

I am estranged from the ideas that animate me. This is the fundamental nature of my bondage, and that of many in today’s world. My mind is filled with the expectations of commanding overseers, the demands of employers, the trends of pop-culture, the compulsions of addiction, the forever keeping-track of everything my brain has capacity for. My brain is at max-capacity, all the time, checking off errands for agendas that have nothing to do with me. Me, as in the things I want without being forced to want them, the moment-to-moment quality of my mind, the physical state of my body, the ideas I might nurture and act on if my resources were not exhausted by external, impersonal demands.

It often feels like only in solitude and betrayal can I find myself. I abandon myself until I feel abandoned by others. Only once I am battered by the ideas of others so abhorrent or demands so utterly preposterous can I stand in my own body, feel the vitality of each cell which I possess, and ask myself clearly: what is there of me beyond all of this reacting, this mimicking, this behaving? And not knowing how to answer this question is what has come to animate me further, deeper, more enduringly than any other idea. There must be an answer to this question, something of substance at my core that is not the product of ideas forced upon me.

I catch myself giving scripted responses to others and I always wince a little. My speech makes its way out without any of me in it. The script, the muscle memory of obedience speaks for me, and I watch. I guess that’s why I’m always vigilantly hovering over the control board of my thoughts and actions–because I hate those moments of being out of my own control. And I guess that’s why I’m so fond of distraction, constant distraction, because in reality, I am always out of my own control. I pull the levers, push the buttons, flip the switches, watch the monitors of the control board diligently, thinking I am the controller. But I fiddle with the controls according to how-to manuals stacked to the ceiling and warning signs posted on the walls and the booming orders of hovering superiors. I am not in control, I am following instructions. And there are too many instructions to keep up with, let alone recall who assigned them to me in the first place, their reasoning, or the severity of the consequences if I make a mistake. No, there is no time to question these things, so I think I am better off safe than sorry, and I pull the levers and push the buttons and flip the switches.

And so it is only when I have done everything right, met every demand, and am still punished despite my efforts, that I can take a moment to question what sense there is in my behavior. Is there any sense in the busy-work of trying to get others to like me? In becoming degreed and salaried? In locking the door while I step out to feel the air? In snapping my head in the direction of any voice that beckons my attention? I have justified wasting my life away meeting others’ demands by clinging to the terror of the consequences of not doing so. And when I ask myself ‘who am I?’ all I can think is ‘I am terrified,’ and once again something deep inside me is awakened by the realization that I have answered incorrectly.

Maybe it is silly to imagine that I am anything at all beyond the conditions from which I have emerged. Perhaps I am only a mind, a meaning-making machine, coupled with worldly conditions and the meaning I extract from them. But don’t I have the right to choose, abiding by the limits of my form, birth, and death, what meaning to extract from these worldly conditions? On account of my arms and legs and eyes and ears and intellect, am I not meant to have freedom in the matter of orchestrating my own fleeting experience? Yes, my arms and legs hesitate and my eyes squint and my ears ache and my intellect falters. But the flaws of my form do not constrict my freedom any more than an empty bank account, or my education, or the thousands of other lame abstractions of greedy institutions do.

I am exhausted by staying within the confines of endless abstractions that I am supposed to believe facilitate life itself. So there is something to be said about exhaustion. What meaning can be extracted from the forty-hour work week where I am bolstering the plague of over-consumption? When I return home, will the four-by-six-foot yard of dying grass in front of my rental unit remind me that I am one with nature? And when my brothers and sisters and aunts and uncles and children and friends are so exhausted by these abstractions that they begin to batter each other, can I still take refuge in kinship? And when our connection to nature and each other is so faint that we slip into psychosis, will drugs restore these bonds? What is there to do when the masses are forced by the ruling class to embody abstract ideas that in theory grant survival and future freedom but in practice fortify the exclusivity of freedom that the ruling class relies on?

Children are made powerless because they are innately free from the hypnosis of societal abstractions. The mind of a child is powerful in its plasticity and freedom from rigidity. We claim to celebrate the adaptability of the young mind, but in reality, it is exploited, constricted, and treated merely as the object of supposedly necessary indoctrination. By convincing parents that the obedience instilled in their children by the education system is personally beneficial, national elites are successful in subduing the natural dissent of a consciously oppressed population. Children are made to be unconscious of their intimate realities through submersion in abstract ideas.

Lesson 1: Prisons keep the good guys safe from the bad guys.

Lesson 2: War is not ideal but often necessary.

Lesson 3: Slavery and genocide are past tragedies we are proud to have overcome.

Lesson 4: Money is the most vital tool for survival.

Lesson 5: Economic instability is a result of personal failure.

Lesson 6: Whether or not you are a failure yourself can be determined early-on through the letters on your report card–so absorb this information good and well, and you will be alright.

The simplicity of these ideas intentionally plays into subjective rationality. We are all aware that there are perpetrators of violence, and in concern for personal safety, it is rational to be glad that there are metal bars confining these perpetrators. We learn about war atrocities and glorify them as the price to pay for the prevention of our own nation’s victimization. Slavery and genocide are defined by our textbooks as past acts of overt violence with precise end-dates, and we assume our morals and awareness are superior to the bystanders of history. We know that an abundance of wealth makes survival easy and luxuries readily available, while the lack of wealth can leave us without food or shelter. We are taught the theoretical framework of economic mobility and are warned against educational failure through the real-life examples of dead-beat drop-outs. Follow the rules of these abstractions, and you may make it to parenthood, where you will enjoy the luxury of believing that your personal authority over your obedient children is indicative of the freedom you’ve been promised in return for your own obedience.

Of course, abstractions are not so convincing to those painfully acquainted with the reality of violence and injustice that underlies these apparently rational ideas. Those who have been affected by the deception of the justice system can see the fallibility of incarceration. Those whose families have been affected by war atrocities, slavery, and genocide can see that the lines drawn in history books between victors and victims has much more to do with the prospect of economic stability than personal success or failure does. Those who are barred from maintaining a livable income despite their life-long efforts can see that the quest for wealth is an exploitative trap. But the ruling class does not worry about the transparency of the fraudulent freedom they’re selling. Their con is only transparent to those from whom it has already stripped political power.

Those who have faith in the notion of government-granted freedom will refuse to contradict the status quo unless they realize that this faith is a product of indoctrination made to prohibit freedom. They will interpret protest of the status quo as a confirmation of government-granted freedom; they think they are witnessing the reliability of a government willing to be criticized. But the government only allows us to protest the status quo so long as our demonstrations do not evolve into real catalysts for change.

We are taught to see the First World as an entity of power and freedom and our own individual freedom as an extension of its domination. And so if we are provided a lesser entity, a powerless child or a supposedly lower-class, to dominate, we are easily tricked into thinking that we are free. We are taught to obey without question as children, and as long as we are rewarded for that obedience and can, in adulthood, assume the role of demanding obedience from others, we can go our whole lives overlooking the oppressive nature of being indoctrinated by the entity that claims to grant our freedom.

So maybe life as we know it, with all its accumulated abstractions, needs to crumble before us. Perhaps at my core, what I am searching for, is my humanity. I know that I am human, intellectually, but that in itself is an abstraction of something I should be feeling, not just knowing. The abstractions of dominating political regimes cloud our humanity–we are rendered obedient and divided and severed from our natural autonomy and kinship. We must see that government-granted freedom is offered in exchange for the innate freedom of our humanity. Freedom granted by a government to the citizens of its nation relies on the exploitation and exclusion of a large sum of humanity without citizenship. We drift from our identification with all of humanity and become consumed by labels that declare superiority over ‘other’ divisions of humanity, leaving us entirely unwhole and wanting.

As humans, we are all striving for meaning. Something to ground ourselves in, something to believe in, something to care about. Mindlessly abiding by societal abstractions means that we accept prescribed meanings of life that do not characterize the truth of our individual or collective humanity. We must not settle for the meanings we are forced to study in school; we must see that the very act of looking for and finding meaning for ourselves is one of the most meaningful characteristics of our humanity in the first place. We must not give up that quest. And if we can embody the freedom to search for our own meaning, I think we will find ourselves bewildered by the abundance of things to ground ourselves in, to believe in, to care about. And we will find those things in each other and in nature, which is not separate from humanity or the individual. The ideas that animate us will come from the intimate consciousness of our collective quest for meaning.